United Nations Environment Programme

North-West Sahara Aquifer System(NWSAS), Phase II

Mid-term Review of the

"Mécanisme de Concertation" component of the

North West Sahara Aquifer System project

Mr. Mark Halle

International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)

Consultant to SDC and UNEP/GEF

Evaluation and Oversight Unit (EOU)

May 2005

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

1.

CEDARE

Centre for Environment and Development of Arab Region and Europe

2.

FAO

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations

3.

FFEM

Fonds français pour l'Environnement Mondial (French GEF)

4.

ISARM

International Shared Aquifer Resource Management

5.

MC

Mécanisme

de

Concertation

(Mechanism for concerted action)

6.

NGO Non-Governmental

Organization

7.

NWSAS

North West Sahara Aquifer System

8.

OAS

Organization of American States

9.

OSS

Observatoire du Sahara et du Sahel

10.

SASS

Système Aquifère du Sahara Septentrionnal

11.

SDC

Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation

12.

UMA

Union du Maghreb arabe

13.

UNECE

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

14.

UNEP/GEF

United Nations Environment Programme/Global Environment Facility

15.

UNESCO (IHP)

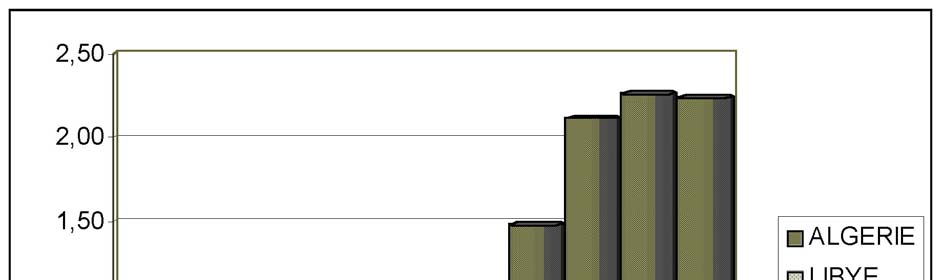

United Nations Education, Science and Culture Organization (International

Hydrological Programme)

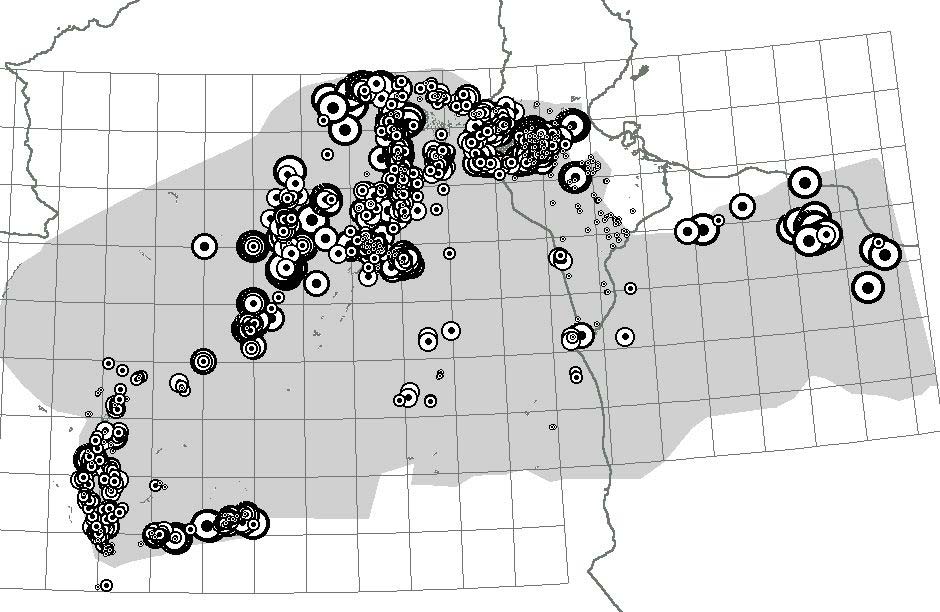

2

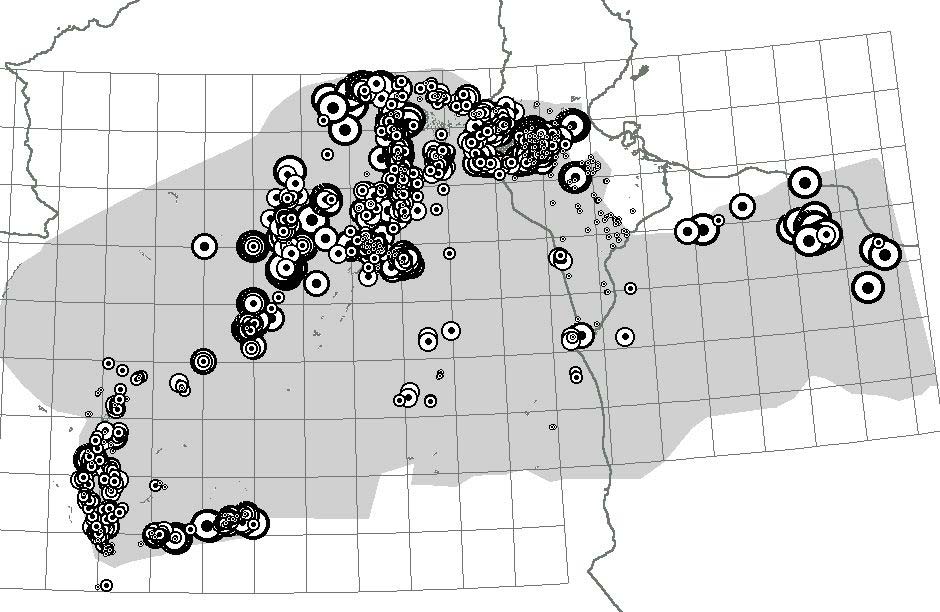

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List

of

Acronyms

and

Abbreviations

2

Acknowledgements

4

Executive Summary

5

I.

Background

to

the

Consultancy

7

II.

A Brief Presentation of the Project

7

III.

Introduction

9

IV.

Approach and Method

9

V.

A

Note

on

the

Meaning

of

Concertation

10

VI.

Evaluation of the "Volet Mécanisme de Concertation"

11

VII.

Lessons learned on Institutional Aspects of Transfrontier Water Management

14

VIII.

Operating Principles of the Mécanisme

de

Concertation

18

IX.

Possible Roles for the Mécanisme de Concertation

18

X.

Institutional Models for the Mécanisme

de

Concertation

21

XI.

Host

Structure

and

Legal

Status

22

XII.

Financial

Considerations

23

XIII.

Staffing

23

XIV.

Conclusions

23

Annex 1 Text of the December 2002 Decision on the MC

25

Annex 2 Examples of Transboundary Water Management Institutions and

Sources of Information

26

Annex

3

People

Interviewed

30

Annex

4

Terms

of

Reference

of

the

Consultancy

31

Annex 5 Presentation of the MC at the Steering Committee in Tripoli,

1-2

February

2005

32

Annex

6

Proposal

for

a

Permanent

Commission

33

Annex

7

Draft

Ministerial

Decision

48

3

Acknowledgements

This consultant operated under the guidance of Hans Schellenberg (SDC) and Takehiro Nakamura

(UNEP/GEF), with support from his UNEP colleagues Catrina Perch and Mela Shah.

The NWSAS project team proved to be both welcoming and open, and their positive attitude went a long way in

facilitating this consultant's work. Special thanks goes to Djamel Latrech, the project director, and to Wafa

Jouini, both of whom went out of their way to make the visits to the region effective and pleasant. I learned a

great deal, also, from some of the hydrogeological experts associated with the project or who have great

experience in the region, and especially Habib Zebidi, Prof. Mohamed Besbes and Bo Appelgren.

The Executive Director of OSS Youba Sokona was supportive throughout, and offered several important

insights that have found their way into this report.

The key partners in Libya, Algeria and Tunisia were perfect hosts. Thanks especially to Rachid Taibi and his

colleagues for the generous hospitality in Algiers.

Finally, all of those interviewed helped me gain important insights on the project. I hope that this report will

offer them something in exchange.

4

Executive Summary

1.

What began as a consultancy to evaluate the component of the NWSAS project relating to the Mechanism

for Concerted Action (MC) evolved to become part evaluation, and part design consultancy for the mechanism to be

put in place before the close of this phase of NWSAS in late 2005 or early 2006. Formally speaking the MC

component of the project could be deemed to include almost all action undertaken in common by the three NWSAS

countries. However, this report focuses on the sub-component relating to the mechanism designed to follow on from

the current project.

2.

The conclusions are based on three different sources of information. The first is a series of interviews with

OSS, the project team, members of national NWSAS steering committees, representatives of the project donors and

international experts familiar with the challenges of rational management of Sahara groundwater. The second is an

extensive review of the project documents, technical and administrative reports, and participation in the NWSAS

Steering Committee (Tripoli, February 2005), in the MC workshop (Algiers, March 2005) and in both the OSS

Governing Board and the Round-Table on Transfrontier Water Management that was organized as part of its

proceedings (Tunis, April 2005). Finally, the consultant reviewed the literature related to transboundary water

management, with a special focus on institutional mechanisms to manage cooperation between countries sharing

water resources.

3.

A short section is devoted to an evaluation of progress in that part of the NWSAS project relating to the

MC. The "Volet Mécanisme de Coopération" comprises four sets of activities workshops for information and

public awareness, mechanisms for data collection and exchange, the monitoring network, and the design of the

permanent mechanism for concerted action. While the scope of the consultancy covers all four, the bulk of the

report focuses on the last of these.

4.

The principal challenge in this respect has been to reconcile two overlapping but substantially different

views. Some see the MC as a permanent materialization of the NWSAS project team (though with slightly different

functions), entrusted with the task of taking the project forward into what is basically a third phase. Others envisage

a light structure focused very centrally on the ongoing cooperation among the three countries in meeting the

challenge of managing the groundwater rationally. While on the surface, there may appear to be little difference

between the two, in fact the differences are significant. As the report argues, the principal difference lies in the

nature of the work to be done. In the first instance, the focus is likely to remain technical, based on the dictates of

hydrogeology. In the latter instance, a shift is effected to an approach more directed at managing the demand for

water - the tools of the former are largely technical; the tools of the latter largely social and political.

5.

The report surveys international experience in transfrontier water management with a view to identifying

best practice and, in particular, lessons from other parts of the world that might be applicable to the NWSAS.

However, it finds that the vast bulk of existing experience relates to shared watercourses and to managing the basins

of international rivers and lakes. The science of transboundary groundwater management is still in its infancy,

though some domestic practice could offer ideas for the NWSAS countries. Although the principles of managing

transfrontier resources generally apply also to groundwater, and whereas early experience in other transboundary

groundwater basins can offer some ideas, NWSAS must inevitably continue to serve as something of a pioneer.

6.

The report proposes a shift in the focus of the proposed cooperative mechanism from one that concentrates

on the supply and present use of the groundwater to one that focuses on managing the demand for that water, and

providing a range of options and incentives to moderate the current dangerously high rates of groundwater depletion.

Such an approach must rest on a solid technical foundation and, inevitably, keeping the database current and

revising and improving the models will require some tripartite cooperation. However, the bulk of the technical work

can and should be undertaken by the national water authorities, and the bulk of the international cooperation

required can be undertaken between countries using the existing system of "Comités mixtes" or "Comités

bilatéraux". If an MC is required, it is largely to coordinate and stimulate a range of activities that the NWSAS has

not undertaken and was not designed to undertake.

5

7.

As envisaged in this report, the MC will shift from a largely hydrogeological approach to one more focused

on translating the implications of the data generated by the NWSAS models into options for decision-making,

particularly tri-partite decision-making among the countries that share the aquifer. The report lays out some of the

principles on which the MC should operate, and suggests both core tasks that the MC should seek to discharge, and

other tasks that it might consider undertaking if the funding can be found.

8.

The principles are largely drawn from international experience in shared water management and from the

field of international water law, but many of them apply more generally to international cooperation on

environmental management.

9.

In terms of the tasks that the MC might undertake, a broad menu is presented, in two priority groups. A

first priority group is regarded as essential if the three countries are to rise to the challenge of controlling demand for

NWSAS water. They include monitoring trends in water use, joint work planning, providing a forum for tripartite

technical or political meetings on key issues, information exchange, the preparation of scenarios, the development of

policy options for decision-makers, and forums to ensure the participation of all key stakeholders. However given

adequate funding, there are many more things the MC might consider doing, even if they are not deemed essential at

this point. These include preparation of issue briefs, publication of an annual review on the State of the NWSAS,

review of water development or other major development proposals in the NWSAS basin, capacity building and

technical assistance, idea generation, action research, and conflict management.

6

North-West Sahara Aquifer System (NWSAS), Phase II

Mid-Term Review of the "Mécanisme de Concertation" component of the NWSAS Project

I.

Background to the Consultancy

10.

Roughly half way through the 27 months of the second phase of the NWSAS project, the principal donor

agencies FFEM, SDC and UNEP/GEF agreed to commission a mid-term evaluation of the project. They agreed

among themselves that FFEM would undertake a formal mid-term evaluation of the technical, socio-economic and

environmental aspects of the project; SDC and UNEP/GEF, together, would focus on evaluating the components of

the project relating to the "Mécanisme de Concertation"1 (hereafter MC).

11.

To that effect, the donors agreed that the two consultants would initiate their work by participating in the

second meeting of the NWSAS Steering Committee (Tripoli, 1 2 February, 2005). In the event, only this

consultant was in a position to participate in the Tripoli meeting. The experience led to a reorientation of the two

consultancies, and of the objectives set for each consultant.

12.

The Tripoli meeting made it clear that, while the three countries of the NWSAS basin have been

cooperating in a commendable manner, from a formal point of view there had not been a great deal of progress in

designing and setting up the MC as envisaged in the project documents that served as the basis for donor support

and funding.

13.

It was therefore agreed that this consultant would reorient his consultancy so that, beyond the relatively

light task of evaluating and commenting on the actions taken under the NWSAS project in relation to the "Volet

Mécanisme de Concertation", he would work with the NWSAS project team to help conceptualize, design and shape

the MC that will need to be adopted by the three countries and put in place before the present phase of the project

winds down at the end of calendar 2005.

14.

It was also agreed that, in view of the advanced stage of project implementation and the slight delays in

bringing the FFEM consultant on board, priority should be given to a final evaluation rather than a mid-term one.

This report therefore focuses on the MC, with no attempt to comment on the overall achievements of the project, or

to rate its progress against the agreed work objectives. Further, while a short section assesses progress in the MC

component against agreed milestones and objectives in the project document, most of the report concerns the

challenges facing the project in terms of promoting tri-country concerted action, ensuring the consolidation and

implementation of the priorities identified by the NWSAS, and contributing to the rational use of the shared

groundwater resources in the interest of sustainable development.

II.

A Brief Presentation of the Project

15.

The project under review is the second phase of the NWSAS project. A first phase was undertaken by OSS

with funding from the International Fund for Agricultural Development and SDC-Switzerland. It was designed to

run for a 36-month period from 1998 to 2000. In fact, the project got underway only in 1999 and concluded in

December 2002. It focused on the following objectives:

Technical

a)

Harmonization of hydrogeological data bases and geodesic data;

b)

Choice of observation network and measurement campaigns;

1 The French term is used because it reflects better the nature and purpose of this mechanism, intended to go further

than simple coordination, but stopping short of any executive function. It implies a mechanism through and by

means of which Libya, Algeria and Tunisia harmonize approaches and actions aimed at making the optimal use of

the NWSAS in the interest of long-term, sustainable development

7

c)

Geological & hydrogeological information collection and analysis of information acquired after 1970;

and

d)

Implementation and calibration of new models and simulation of exploitation scenarios.

Consultation Mechanism

e)

review of existing technical & scientific consultation commissions and appropriate strengthening of

these bodies towards the above objectives;

f)

regular information exchange;

g)

joint elaboration of simulation models;

h)

analysis of the internal legislation of each country (laws, regulations);

i)

joint analysis of existing water monitoring & control systems; and

j)

joint assessment of pertinent institutional capabilities and training facilities in place in each country.

16.

Based on the above, the project aimed to draw up a set of concerted specific water resource regulations at

the technical level with the appropriate institutional arrangements for consideration by the respective authorities in

each country. For this purpose, a consultation mechanism between the three countries was to be set up as a

permanent institution.

17.

Finally, with assistance from OSS and the Legal Bureau of the Development and Legislation Department of

the FAO, the project aimed to prepare an Inter-State Arrangement implying the adoption of common policies and

goals for the long-term management of the Northern Sahara Basin water resources.2

18.

The first phase resulted in an integrated vision of the aquifer basin and set in place a culture of information

exchange and common problem solving among the three countries that share it. Finally, it helped to identify and

reinforce the capacities in the three countries in a number of important areas relevant to the project's objectives.

19.

More specifically, it put in place an information system on the aquifer, designed a model of water use based

on this information, and used the model to simulate a range of scenarios on water use. It enabled the countries to

identify the most vulnerable zones within the NWSAS basin. And it secured the agreement of the three countries on

the design of a mechanism for concerted action among them.

20.

It reached the following conclusions:

· continued use of the NWSAS groundwater resources at present rates represents a grave danger for the

aquifer and for certain sensitive ecosystems;

· in some areas a slight increase in water use might still be envisaged;

· the scenarios based on upper-range calculations of water use would lead to an unacceptable situation;

· there are still unexploited stocks of water, especially in Western part of the basin, but their use would imply

large-scale transfers to populated areas;

· despite the results achieved in the project, important uncertainties and gaps in knowledge persist, both on

the assessment of the situation and on the possible solutions to known problems.3

It was thus deemed necessary to extend the project into a second phase, which benefits from the support of

UNEP/GEF (US$ 600,000, under execution since May 2003 and due to be completed in July 2005); FFEM (US$

2 Description of Phase I taken from the SDC internal summary of the funding request dated 6 February 1998

3 This assessment of the results of Phase I were adapted from the FFEM project document for Phase II.

8

300,000, under execution since July 2004) and SDC Switzerland (US$ 400,000, under execution since January

2003)4.

21.

The objectives of the second phase of NWSAS are as follows5:

a. Hydraulic component: aimed, on the one hand, at supplementing knowledge of the basin and, on

the other hand, at conducting further in-depth studies on the risk zones.

b. Socio-economic component: aimed at a better analysis of the consequences of the abstractions on

the populations, the exploitation modes of the resource and the environment. Effort was also to be

focused in particular on the wetlands and salty soils.

c. Environmental component: aimed to characterize the impacts of the abstractions on the

environment, with a special focus on wetlands and salty soils.

d. Information system component: aimed at consolidating the acquired knowledge and experience of

phase 1 by integrating the data generated by the other components, and at defining the modes of

administration, data exchange, as well as a firm establishment of the information system.

e. Consultation mechanism component: aimed at the setup of consulted basin management modes

based on a structure that is firmly established on the institutional and legal levels with clearly

defined prerogatives.

f. Monitoring-Evaluation component: relates to the administrative management of the project

ensured by the OSS.

III.

Introduction

22.

The Mécanisme de Concertation has been a component of both phases of the NWSAS project. A meeting

held at FAO headquarters in December 2002, at the end of the first phase, focused specifically on the design and

purpose of this MC. The text of the decision taken at that time is included in this report as Annex 1. Already then,

the MC was seen as the vehicle that would ensure further cooperation among the three countries following

completion of the forthcoming second phase of the NWSAS project. The two-year period of the second phase

coincided with the time deemed necessary for the MC to be agreed, designed and put in place. Doing this would

ensure a seamless transition at the conclusion of what was seen as the final phase of large-scale donor support to the

process of planning the management of the aquifer with a view to promoting sustainable development in the basin.

The clear assumption was that the MC would be up and running when the second phase of the project came to a

close, so as to ensure no loss of momentum in facing the challenge of managing the groundwater rationally.

23.

For this reason, the MC was included as a specific component of the Phase II project proposal, and a series

of specific actions were included in the project's work plan. These components are summarised in Section 5 of this

report, with a brief assessment of progress made in each. Broadly speaking, little attention was paid to the design of

the MC in the first year of the project. Tripoli served as a wake-up call in this respect, and a period of frenetic

activity followed. This period coincides with the period of this consultant's contract, such that this report comments

to a large extent on a process that was constantly developing and changing as the consultancy progressed.

IV.

Approach and Method

24.

The analysis and recommendations below are based on three principal sources of information: first, an

extensive review of the documentation relating to the project project documents and reports, commissioned papers,

4 These figures and dates are taken from the draft TOR provided to the consultant by SDC and UNEP/GEF. _They

are at some variance with the figures contained in the FFEM project document, though the proportions remain

similar.

5 Taken from the report of the NWSAS Steering Committee, second meeting, Tripoli, 1-2 February 2005.

9

technical documents relating to the aquifer, and material from earlier projects in the area, including the first phase of

the NWSAS project. Second, the consultant reviewed some twenty technical and policy sources relating to

management of shared aquifers, river basins or fossil groundwater resources. The most relevant of these sources,

with the web links where appropriate, are listed at Annex 2, together with an indication of where to look for

examples of transfrontier water management institutions. Finally, the consultant conducted over twenty interviews,

including most of the members of the national Steering Committees in the three countries, key experts from the three

countries, and representatives of donor agencies and intergovernmental organizations. Of these, more than two

thirds were extensive interviews, lasting over an hour. A list of those interviewed is attached at Annex 3.

25.

The consultant also attended the annual NWSAS Steering Committee meeting in Tripoli in January-

February, participated actively in a special workshop on the MC, held in Algiers in mid-March as well as the OSS

Executive Board meeting in Tunis in early April, including the Round Table on Transfrontier Water Resources

Management.

26.

The consultant's Terms of Reference are attached at Annex 4. They were prepared by SDC and

supplemented by UNEP/GEF and represent the view of the "evaluation" as it was initially conceived, and covered

the task of a two-person consultant team. As events unfolded, two factors affected the strict relevance of these TOR

as a road-map for the consultant. First, while it was initially intended that the two consultants work as a team, in

fact this did not prove to be possible. Second, following the Tripoli meeting, it became clear that an evaluation of

the MC is not the principal contribution needed at this stage. As a result, the consultant's task was shifted, with

agreement of the two sponsors, to one that combined elements of evaluation with elements of design of the future

MC. In this respect, the TOR included at Annex 4 are no more than an initial guide, supplemented with a number of

e-mail exchanges and with long discussions with the SDC and UNEP/GEF representatives at the Tripoli meeting, in

concert with the FFEM representative.

V.

A note on the meaning of "Concertation"

27.

There exists a broad spectrum of opinion and understanding relating to the need for, the role and the ideal

shape of the MC, as well as the importance of what has been achieved so far. Unpacking the different perspectives

has been one of the challenges of the consultancy.

28.

First, there is a gap between what the project team regards as having been achieved in the current phase of

NWSAS and the expectations of the donors. Second, there is a gap between notions of what is required to ensure

continuing cooperation among the three countries and what is required to manage the shared aquifer optimally.

Third and finally, although the Algiers workshop and the Tunis Roundtable brought positions closer, there remains

an ambition gap in terms of the design and scope of the MC to be put in place by the end of this phase of the

NWSAS project. Each of these is addressed separately below.

a)

What has been achieved in NWSAS II

29.

"Concertation" connotes parties working together to achieve a shared goal. In that sense, the entire

NWSAS is an effort at "concertation" and the project structure itself might be regarded as an MC. There is a

tendency in the NWSAS project team to chalk up all common action undertaken during this phase of the project to

the credit side of the MC's balance sheet. Since the three countries are working together in a spirit of harmony,

sharing information, and constructing a common database they are, in fact, acting in concert. The implication,

though it is nowhere stated in this manner, is that the MC should carry forward all essential aspects of the NWSAS

that require further cooperation. It is thus in some ways confused with what might normally be regarded as a third

phase of NWSAS, though at a more modest level of funding.

30.

The donors and others interviewed, while saluting what has been achieved, point to the need for a structure

that will continue to act following the conclusion of the NWSAS project and to undertake a specific set of duties to

anchor and consolidate what has been achieved in the two phases of the project and to favour the optimal use of the

shared groundwater resource. This thinking suggests that the NWSAS project will reach its conclusion at the end of

the present phase, and will be followed by two forms of action first, by action relating to the challenge of rational

management of the NWSAS groundwater resource built into and carried out by the national authorities in the three

countries that share the basin, in principle without the need for further technical or financial support from the donor

10

community. The second form of action would revolve around the MC, an autonomous, light structure that focuses

entirely on those issues that require information sharing, joint decision-making and common action by the three

countries. The donors do not conceive of this as a new phase of the NWSAS project, nor do they believe it need

necessarily require continuing support from the donor community.

31.

These two visions are no longer very far apart. There is consensus on the need for a light structure, of one

coordinator and perhaps one or two junior staff. There is consensus on the need for the three countries of the

NWSAS basin to cover all or most of the expenses of such a structure. Where there is a difference of opinion, it is

in the initiation and executive functions of the structure.

32.

It appears important, while commending the positive and cooperative atmosphere that the project has

helped to put in place among the three countries, to return to a more specific notion of the MC, starting with the

tasks set out in the project document and then focusing on what needs to be in place before the end of the project so

that its achievements will not unravel.

b)

The MC and the wider needs of further work on the NWSAS

33.

In the course of the interviews, a major difference in perspective became clear. The donor community, in

keeping with the decisions in this respect taken at the Steering Committee meeting in Tripoli, envisage a light

structure focused on issues that require concerted tri-country action, that studiously avoids overlap with national

water authorities in the three countries, and that is sharply focused on serving as a bridge between the technical

assessment of the aquifer and the political decisions that need to be taken to ensure the optimal use of the

groundwater resources. Others, and in particular the project team and the Algerian national water authority, are

concerned that the conclusion of the current phase of the project will leave the technical work incomplete, with the

risk that some of what has been achieved or is within reach will begin to unravel, leaving the countries poorly

equipped to face the challenge of optimal management of their shared resource. As a result, they tend to conceive of

the MC as having a dual purpose that envisaged by the donors and other proponents of a light mechanism, and that

of ensuring essential project follow-up.

34.

This is an issue that the donors, the OSS and the countries must address head-on, but it is here

recommended that the MC that is envisaged as kicking in and continuing after the project be kept separate from the

debate on whether further technical assistance is required to bring the challenge of managing the NWSAS to the

point where it can be assumed by the three countries themselves, supported by the MC. Perhaps answering this

question should be one of the tasks of the consultancy to be organized by the FFEM later this year.

c)

Scope and Role of the MC

35.

Following from the discussion above, it is recommended that the design of the MC and the need for a

further phase of work on the NWSAS project be regarded as separate and independent issues, with only the first

being addressed in this report. This recommendation stems from two related observations: that the project has

reached the stage where a light MC could begin to play a useful role even if no further support is forthcoming for

technical assistance related to the NWSAS; and that the proper task for the MC requires skills that are

complementary to but different from those required in the two phases of the NWSAS project, or that might be

required for any future tri-country effort to complete the technical work on the aquifer.

VI.

Evaluation of the "Volet Mécanisme de Concertation"

36.

This component of the project is set out at pages 29 and 30 of the project presentation6. It comprises the set

of activities described under the code WP 50000, and includes four principal groups of activities: WP 51000 -

Ateliers d'Information et Sensibilisation; WP 52000 Modalités de collecte et d'échanges de donnés; WP 53000

Réseaux d'observation; and WP 54000 Mise en place de la structure permanente de concertation du SASS. The

first three might be regarded as activities built into the regular work of the project, while the fourth relates to the

design of the mechanism to operate beyond the closing date of the project.

6 Rapport de Présentation, Système Aquifère du Sahara Septentrional, Secrétariat du FFEM, Novembre 2003

11

37.

The objectives articulated for this component of the project are as follows:

· L'institutionnalisation de la structure de concertation permanente du SASS;

· L'implication de tous les partenaires et acteurs du bassin;

· La valorisation des résultats du projet et leur appropriation par les différents décideurs et partenaires;

· L'aboutissement à des accords concernant:

L'implémentation de la base de données commune avec les protocoles d'échanges, de mise à jour

régulière et d'administration

Les réseaux communs de surveillance et les modalités d'échanges et de gestion

Les procédures pour la réalisation de simulations périodique

La mise en oeuvre des recommandations issues de la présente phase du projet SASS.

38.

Evaluation of the first three components (WP51000, WP52000 and WP53000) is made more difficult by

the vagueness of the language that describes them, and the fact that they are indistinguishable from the regular work

programme of the project itself. Thus the second and third components relate directly to the technical work

programme, and are mechanisms for concerted action only in that the three countries must agree on how data are

gathered and exchanged.

39.

The second component (WP52000) is strictly focused on an agreement between the three parties on how

data are collected and exchanged among them. Had they not agreed on how data were to be collected and

exchanged, there would have been no project. The fact that they have agreed, at least at some level, is an

achievement for the project, but an achievement for the MC only in the sense, noted above, that the entire project is

an enterprise in cooperation. To reinforce this point, the report of the Second Steering Committee meeting of the

NWSAS in Tripoli (1-2 February 2005) sums up the achievements of technical, environmental and socio-economic

components of the project as advances for the MC. Evaluation of this element has little value in terms of

understanding the MC, although it will be an important component of any technical evaluation of the project and as

such will be undertaken by the consultant evaluating the technical achievements of the project later in 2005.

40.

The third component is not much more useful. The sole purpose of this component is to agree on a

monitoring network and to ensure that it is "adopted" (pris en charge) by whom is not specified, but one can

assume it is the national water authorities in the three countries. Agreeing on this network, and on the protocols for

data collection, is an essential precondition for the technical components that form the backbone of the project.

Without cooperation among the three countries on this point, one could conclude that the MC (as understood here)

did not function. But noting that the three countries did indeed cooperate on this point says no more than the fact

that the entire NWSAS project was a vehicle for the three countries to cooperate a remarkably circular argument.

41.

The first component is in a sense more robust and susceptible to opinion-forming. Throughout the project,

workshops would be organized so that the entire range of stakeholders could discuss the results of the work

undertaken in the other components of the project. The principal vehicle for this purpose appears to be the

formation of national Steering Committees (Comités de Pilotage) in the three countries. In these, the water

resources authorities have invariably been well represented. Each has included representatives from the

Environment and Agriculture sectors, though in many cases the representatives from Environment and Agriculture

have a hydrogeological background and are those officials responsible for hydrogeology in their respective

Ministries, and are in some cases former staff of the water agencies! Some have included academic experts (e.g. in

Libya) and some NGOs (e.g. in Tunisia and Algeria).

42.

A common feature of these Committees has been their confusion as to their purpose. When this

consultancy began (in January 2005), the three committees had been formed, and had held their first formal meeting

(in Algeria in July 2004, in Tunisia and Libya in November 2004). These meetings consisted of a presentation of

12

the NWSAS project by the project team and a discussion of the role of the national steering committees. Despite

this latter feature, the overwhelming impression given by committee members only a few months later is that there

remains considerable confusion about what is expected of them, individually or collectively.

43.

While individual members of these Committees have continued to interact with the project some

frequently and whereas members of these Committees have been privileged invitees to NWSAS events such as the

annual Steering Committee (though usually those members from the water resources sector) their next formal

convocation was to the MC design workshop in Algiers, mid-March 2005. One must conclude that they have not

been much engaged in the project as Committees although, as I note above, they have often been close to the project

as individuals, some even serving as consultants to the project.

44.

Project staff have had many occasions to present the project in different forums in the region and

elsewhere. Indeed, the NWSAS project is regarded by OSS as its flagship project, indicative of the role that OSS

can play as a convener, a source of technical advice, and as a forum for multi-country concerted action. While no

doubt these sessions generated sporadic feedback and ideas, it is hard to consider this series of rather ad hoc

activities as anything more than public outreach and communication. While they may formally fulfill the

requirements of the project document and attendant donor contracts, it would be a stretch to consider them much of

a contribution to the MC during the life of the project, much less to the preparation of the coming post-project

activities.

45.

There are, thus, two general statements to be made concerning the first three components of this part of the

project. The first is that the NWSAS project itself is designed as a cooperative venture among three countries. Not

only its success, but any significant progress whatsoever, depended on securing a minimum degree of concerted

action among the three countries. The fact that the project has established a technical foundation permitting an

aquifer-wide monitoring and management is an indication that concerted action has taken place. In this consultant's

opinion, however, it is invidious to regard these (with the partial exception of first component) as genuinely

belonging under the heading of the MC. This, however, is a fault of the project design as much as of the project

team itself. With respect to the first component, the performance of the project team is generally lackluster. Much

more could and should have been done to mobilize the national steering committees and to use public workshops to

table the key issues faced in managing the aquifer rather than to promote the project itself.

46.

The second general statement is that, to evaluate what has been achieved in the second and third

components, it will be necessary to evaluate the merit of the technical work undertaken by the project, and the

opinion of it held in the three countries. This will be the task of the consultant evaluating the project later in 2005.

47.

This leaves the fourth component concerned with the design of the mechanism for NWSAS follow-up.

The foundation for this is the Rome text, attached at Annex 1. The more formal-minded within the project team

consider this to be in the nature of a tripartite agreement, a legal text whose provisions should be departed from only

in the direst of circumstances. Others regard it as an indication of the outlook and understanding that existed at the

conclusion of the first phase, to be built upon, matured and taken forward as one of the key challenges at every stage

of the second phase.

48.

Whatever the truth, it is clear that a limited amount of thought was given to the MC (that is, to the MC to

replace the project at the end of its second phase, or the fourth component of the "Volet MC" in the project

document) in the first year of the second phase. The reasons for this are probably multiple: the nature of the project

team, much more at home in the hydrogeological elements of the project than the social and political process

elements; a belief that the Rome text could serve as the basis for the MC, and a belief that a focus on the MC was

more appropriate for the second year of the project than for the first. The Steering Committee in Tripoli in January-

February 2005 served as an alarm bell for the project team. The presentation of the MC component of the SASS

project (attached at Annex 5) is thin on content and reflects limited thinking on the future of the NWSAS initiative

beyond what was established in Rome before this phase of the project started.

49.

At this stage of the game, it would have been easy for this consultant to conclude that the "Volet MC" was

characterized by a confused and somewhat wooly set of objectives that made it difficult to distinguish this work

from the core activities of the project, a lack of a robust framework against which to evaluate progress, and

disappointing progress in those elements that stood out as clear and distinct from the rest of the project. This critical

13

comment would have reflected poorly not only on the project, but on the project document and, by extension, on the

donors who accepted it in its present form.

50.

However, at this stage, the consultancy moved from being a fixed-point evaluation to an effort at

collaborating with the project and with OSS on the design of the "follow-up MC". From this point on, the challenge

has been to follow, contribute to and, at the same time, assess the value of, this component of the project, a

challenge made more difficult in that work on this component took off and advanced considerably in the two-month

period from the Tripoli meeting until the OSS Executive Board meeting in early April.

51.

This report therefore offers the comments above as the evaluation component. The rest of the report will

offer input to the final design of the MC, much if not all of it discussed extensively with the project team, but not all

of it taken on board at the time of writing.

VII.

Lessons Learned on Institutional Aspects of Transfrontier Water Management

52.

Although inter-community cooperation on water management dates back to 2500 BC, with the agreement

that ended a water war between the Sumerian cities of Lagash and Umma over use of the Tigris river, the science

and politics of water management has advanced by leaps and bounds in the past two decades. International water

law has gone through a quantum leap in development, and the international institutional landscape has been

populated with new international institutions dealing with the global challenge of water supply and use. Water is

now accepted as having a central place in meeting the challenge of development in the poorest countries, and it

appears in first place in the various articulations of our global development priorities, including the Millennium

Development Goals.

53.

Much of this attention is focused on the management of transboundary watercourses. Both in the

intergovernmental organizations and in the academic world, a great deal of attention has been paid to legal and

institutional arrangements, conflict management or avoidance, and to what works and what does not work in

transboundary water management. This analytical literature is widely available and is augmented constantly.

54.

In view of the surge in international interest in water issues, it is somewhat surprising how little attention

has been paid to transboundary groundwater resources, and in particular to shared fossil water sources, particularly

since ground water is today the most extracted natural resource in the world. While the United Nations

International Law Commission is in the process of developing elements of an international law on transboundary

groundwater resources, and while the International Shared Aquifer Resource Management project (an initiative of

UNESCO's International Hydrological Programme in partnership with FAO, UNECE, the International Association

of Hydrogeologists, the Organization of American States and OSS) is in the process of publishing a book on various

aspects of international groundwater management7, very little experience exists in transboundary aquifers, and

almost none on the management of shared fossil water resources. While there are some 117 international

agreements covering shared water basins, there is only one that directly addresses a transboundary aquifer.8

55.

While some of the lessons learned from transfrontier water management are applicable to the NWSAS,

much of it is not. In this respect, the SASS is breaking new ground. On the one hand this renders the project even

more important and significant than it already is in its regional context. On the other hand, however, it means that

the project is to some extent feeling its way in the dark. The rest of this section seeks to draw from international

experience some of the key lessons learned that might offer guidance to SASS as it finalizes the design of the MC.

· Despite earlier fears about "water wars", competition over shared water leads more often to cooperation

than to conflict. In cases where conflict has resulted, it is almost always in shared water systems where no

institutional mechanisms for cooperation had been established. In other words, institutions established with

the purpose of promoting inter-country cooperation are a significant factor in ensuring positive rather than

negative outcomes.

7 Personal comment by Dr. Alice Aureli, UNESCO-IHP

8 An agreement between France and Geneva, Switzerland.

14

· Positive cooperation over shared water resources is most often successful when a mix of regulation and

incentives is used. Since direct regulation of individual users is often politically and practically impossible,

it is usually necessary to create user-based organizations or informal social mechanisms that provide

individual users with incentives to use the resource prudently. For this, experience worldwide shows that

public participation in reaching decisions is crucial for positive outcomes.

· Successful models tend to spell out in some detail the procedures that will be followed to resolve any

dispute that might arise between the parties.

· Joint management of shared water resources, and in particular those matters that require explicit decisions

and commitments by the different parties, requires the search for win-win solutions, in which all parties

will find a mutual interest.

· The three requisites of successful international water cooperation are: active support from the top level of

the political leadership; mobilization of the available expertise; and a domestic government structure

capable of effective international cooperation and collaboration. That said a formal structure for

cooperation is not in itself a guarantee that a high level of cooperation will be achieved.

· It is important to identify and map areas of disagreement between parties, and to develop a work plan that

progressively moves countries towards a consensus on these issues.

56.

While the above summary distils some of the lessons from shared river basin management that are

applicable to management of shared aquifers, it is striking how little there is that applies directly to them. Much of

the recent literature on shared water courses focuses on the new approach of sharing the benefits from use of the

water, rather than simply apportioning the water itself. The institutional mechanisms are focused principally on

monitoring water and water use, providing a forum for allocation and sharing of the benefits, and managing any

incipient conflict that may arise from differences of opinion between parties to the agreement.

57.

Yet with groundwater, and in particular with fossil water stocks, notions of sustainable use, benefit sharing

and other central principles of transfrontier water management do not really apply, or at least they do not apply in

the same way. To cite the ISARM Framework Document: "Large aquifers can, however, extend across multiple

geographic, administrative and political regions. In this situation, local agencies generally have little hope of

influencing regional groundwater conditions through isolated actions under their direct control. While inter-

country dialogue may be primarily driven by regional development and the role of regional markets, the local

patterns of use and opportunities for effective management are more likely to be a function of local needs and

solidarity. The institutional mechanisms that will deal with transboundary aquifer issues therefore need to

differentiate between the domestic management regime and that required for international management

(emphasis added)."

58.

In the case of the deep aquifers of the NWSAS, sustainable use is not possible. Natural recharge of these

aquifers is well below present use (see figure below), and options for artificial recharge are unrealistic in most of the

basin. Further, there is little scope for increasing demand on shallow aquifers. Indeed, these are in places at risk

from the extraction of water from the NWSAS and a threat to artesian wells has been noted throughout the basin.

And while there is some experimentation, especially at the northern fringes of Algeria's NWSAS basin, to increase

artificial recharge of aquifers, nobody believes this can make more than a marginal difference to the overall picture

of NWSAS water uses. Instead, the challenge is for the countries to agree on the rate of use, how the water is used,

and how this agreed rate is policed.

15

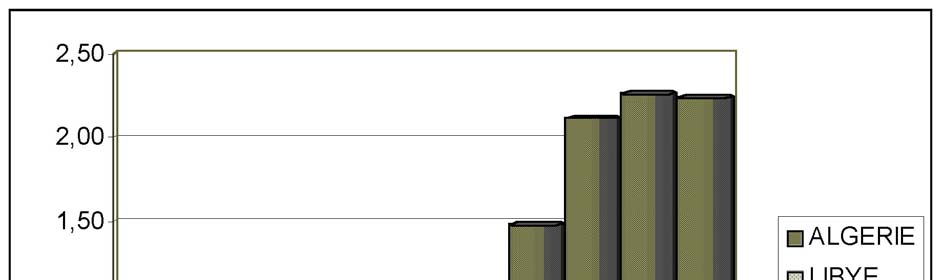

EVOLUTION DES PRELEVEMENTS

PRELEVEMENTS TOTAUX DANS LE SASS,

Milliards m3/an

2,7

2,4

2,1

1,8

1,5

LIBYE

TUNISIE

1,2

Prélèvements > Recharge

ALGERIE

0,9

0,6

0,3

FIDA

0

17- 18 / 02/04

1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

Rome

59.

Further, the water in the NWSAS is not "shared" in the usual sense of the term. The aquifer is not so much

an underground river as an underground lake. Water exchanges between countries are so slow as to be insignificant.

Each country takes "its" water out of the ground, not the water of its neighbour. The transfrontier impact is felt

through a generalized lowering of the water table.

60.

How significant, then, is the transboundary nature of the issues to be addressed, and how are they different

from the "shared" issues (those that appear in each of the three countries)? Current use, and even more so the

anticipated growth in use, has the effect of lowering the water table, making pumping more difficult and more

expensive, and aggravating the risk of undesirable environmental impacts such as reversing the water flow in the

Chotts, groundwater contamination or water-logging of agricultural fields. Extracting water in one country does not

in any significant way capture water that would have flowed over the frontier for potential use in another. It does,

however, significantly add to the challenge of water extraction and management in the neighbouring country as a

result of the generalized lowering of the water table. Further, the risk for certain ecosystems and natural areas

including transfrontier Chotts and wetland areas is significant. There is a genuine fear that we are approaching

thresholds beyond which the water flow in the Chotts could be reversed and saline water invade the deep aquifers,

rendering them unusable for human or agricultural consumption.

61.

Patterns of settlement and agricultural development also affect the demand for NWSAS water resources, as

do plans for large-scale water diversion. Libya's plan to extract large quantities of groundwater in the Ghadamès

area at the frontier of Tunisia and Algeria for transport to the Libyan coast is the subject of considerable concern

among its neighbours. Similarly, the recent boom in agricultural development and the attendant spread in settlement

in the Biskra area of Algeria has led that area to be identified as one of particular focus for the NWSAS project.

62.

Finally, suspicions over neighbours' plans for water development are a source of political tension and have

the potential to flare up quickly given the right sort of trigger. Transboundary cooperation in the form of regular

contact, information sharing, joint modelling, joint planning and the other tasks envisaged for the MC could play an

important part in avoiding any water-related issues escalating into a source of political dispute and thus undermining

efforts at cooperation.

16

63.

So, while all of this justifies a mechanism for permanent transboundary cooperation, it is not a challenge at

the same level as the allocation of access rights to the water that crosses the frontier. Sound management requires

enforced agreements on rate of use, but not on sharing the benefits that derive from that use.

64.

Finally, in the particular case of the NWSAS, the notion of conflict is politically sensitive in the extreme.

Given the history of the region, any difference of opinion between or among the countries is immediately elevated to

the highest political level and becomes a matter for the Foreign Ministries. It could be a long time before it is

acceptable for a water-based authority to manage even minor conflicts between countries.

65.

The search for models in other parts of the world has also proved fairly fruitless. While other regions are

developing cooperative institutional models for groundwater management, most are no more advanced than

NWSAS or, where they are, it is too early to determine whether the models work. The Nubian Sandstone Aquifer

between Libya, Egypt, Sudan and Chad is hosted by CEDARE (the Centre for Environment and Development in the

Arab Region and Europe) and, while it has been in existence longer than NWSAS, it is remarkably difficult to

encounter reliable and relevant information on the nature of the cooperation that takes place among the countries

that share the basin. Those interviewed were categorical in declaring that there was nothing to be learned from this

example.

66.

The Guaraní Aquifer project (GEF/OAS) in Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina is more often held up

as an example that is developing in parallel with the NWSAS, but its institutional mechanisms, too, are in their early

stages and there appears to be little objective basis for judging the cooperation that has resulted from these

arrangements. The Guaraní Aquifer project follows a classical model of transfrontier cooperation by including a

Collegiate Coordination Committee comprising the project director, the chairs of the national committees, and a

representative of the Organization of American States. The national committees are different from those in the

NWSAS project only in that they include representatives from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs. One area where the

Guaraní project has innovated is in the setting up of two funds one a University Fund that sponsors research

relevant to the management of the aquifer, and one a Citizen's Fund, which appears to be a small-grants facility

open to local students, leaders and activist groups. Something similar should be considered for NWSAS, although

the cultural context in North Africa is substantially different.

67.

The more relevant experience, in some ways, comes from what has been done in certain individual

countries. The Kansas State Groundwater Management Districts Act in the United States, for example, allows local

land owners and water users to take their own decisions about groundwater management issues, as long as they form

a legally-constituted Groundwater Management District (whose requirements are set out in the Act) and operate

within the rules of that body. This, in effect, creates a collective of stakeholders who agree on the rules of water

access and use among themselves, and subsequently police their members.

68.

In Mexico, an experiment is underway with Groundwater Authorities, each responsible for a given

groundwater resource. While these are established on the basis of geographical regions and not on the basis of user-

groups per se, the notion is the same that a given group of stakeholders, who share an interest in both access to and

rational management of the groundwater, are given specific authority over the resource.

69.

This model might well apply to areas within the NWSAS, although it would be somewhat far from the

current, heavily administrative approach inherited by the three countries upon their independence. It is a model not

by any means confined to the world of water. Indeed, it is an increasingly common approach to the management of

common property resources. Users are grouped into recognized units and given access rights in exchange for

abiding by agreed rules. There is a strong built-in incentive to respect the rules, in that the consequence of not doing

so can be the loss of access by the whole group, immediately or on a longer-term basis. The institutional mechanism

that brings the users together also provides a vehicle for participation in decision-making in respect of the resource,

for sharing of knowledge, and for continuous monitoring of the impact of the management measures.

70.

These examples and they abound in the world of fisheries, forests, wildlife and other open-access

resources applied to groundwater, suggest that the national institutions responsible for groundwater management

must work in concert with legal and regulatory frameworks that allow local users to develop management

approaches suited to the local conditions, and at the same time provide a forum to deal with the higher level policy

17

issues relating to groundwater use, especially those that have international implications. The latter constitutes the

niche for the MC.

71.

If this last paragraph is taken as a recommendation, it has far-reaching implications. It suggests, for one,

that the MC envisaged in the project and in this report can address only part of what is required to bring water use in

the aquifer basin within rational limits. These are spelled out in some detail in section 8 below. Thus the MC would

on a concerted basis among the three countries - focus on putting in place the range of institutions, regulations,

policies and incentives in the three countries that would render possible the second set of actions, this time at the

local level, of organizing water users within a series of loose institutional frameworks that would give them both

rights to the water resources, and a shared responsibility for ensuring its rational management. This sort of

approach, while full of promise is still, one suspects, distant from the predominant political and administrative

culture in the three countries sharing the NWSAS. Nevertheless, to the extent the MC is successful in its principal

functions, it would prepare fertile ground for the sort of political and social experimentation that, in the end, will be

required if the NWSAS is to be managed wisely.

VIII. Operating Principles for the MC

72. The

NWSAS

Steering

Committee in Tripoli agreed on the establishment of a light structure (structure

légère) to ensure appropriate harmonization of policies and approaches among the three countries in their quest to

ensure the optimal development of the aquifer. While the degree of lightness is not yet a matter of consensus, there

is agreement that the MC set up in the first instance will be a flexible, minimalist setup that will develop and

respond to changing needs. There is also agreement that the bulk of the work needed to follow up the two phases of

the NWSAS must be undertaken by the authorities in the three countries of the basin, and that this must be built into

the regular work programmes of the relevant agencies in these countries. The MC is to be established to address

those needs that cannot adequately be handled by the countries themselves and which, if ignored, will undermine the

prospects for rational management of the aquifer.

73.

Before considering the structure and activities of the MC, this section will set out a number of principles,

assumptions and shared understandings on the basis of which it is recommended that MC operate.

74. The

MC:

· will consolidate and build upon the key achievements of the NWSAS project

· It will not undertake work more appropriately carried out at the national level

· It will bring clear added value to the work undertaken by the national authorities in the three

countries

· It will be neutral and non-partisan as among the interests of the three countries

· Its will focus on the priorities and the decisions that require harmonized and concerted decision-

taking by the three countries

· It will respect the principle of subsidiarity namely that decisions should be taken at the lowest

jurisdictional level possible consistent with efficacy

· It will focus on preparing options for decision makers and not on taking these decisions.

IX.

Possible roles for the MC

75.

In keeping with the principles suggested above, and with a view to respecting the Tripoli decision in favour

of a "light structure", the following tasks for the MC are suggested, grouped into the central tasks, and others that

might be taken on if funding and capacity should permit.

Central tasks

· Monitoring, trend identification, tracking of key indicators such as water demand, population

in the NWSAS basin, patterns of agricultural development, settlement, etc. This involves

ensuring that the three countries agree on the nature of the data to be gathered, maintain their data-

gathering activities and report the information to the MC, that maintains up-to-date databases and

18

applies the data to the model, in order to provide the raw material for scenario-building. It can be

anticipated that the data currently being gathered and maintained is insufficient for the purposes of

rational management of the aquifer and will, over time, be supplemented by other categories,

datasets, etc. The MC's role is not to gather the data but to provide ongoing encouragement to

countries to gather and provide it, and then to collate and analyze it so that it can serve as an optimal

foundation on which sound policy decisions can be built.

· Joint planning and work plan development among authorities in the three countries.

Coordination of relevant aspects of the work programmes of the water, agriculture, rural

development, environment and other national authorities could maximize synergies and ensure that

national activities tend towards a common goal. This component of the work of the MC should

focus strictly on those activities critical to the rational management of the groundwater resources,

where divergent approaches and priorities could undermine this goal. The achievement of this task

implies both the continued existence of a functioning mechanism for concerted action at the national

level (perhaps based on the Comités de Pilotage formed under NWSAS), as well as a regular forum

in which the three countries can meet.

· Scheduling and organising regular technical, policy-level or ministerial meetings among the

three countries on priority issues relating to the aquifer. Following on the last task, the MC

could serve a useful role in promoting or actually organising tri-partite meetings on key issues

relating to the aquifer. The function of the MC would be to bring the relevant parties together

around a given topic, to provide the background needed for sensible decision-making (scenarios,

draft policy options, analyses), to record and, if appropriate, to publicize the results of these

deliberations.

· Exchange of information among the three countries: maintaining the database on NWSAS,

operating the model developed, receiving and collating reports from the authorities in the three

countries, and tracking relevant developments in other parts of the world will make the MC a

switchboard for information. It will be essential that this information makes its way effectively, in a

timely and targeted manner to those who require the information and are able to act on its basis.

· Scenario development: operating the database and applying the model will allow the MC to draw

up a range of scenarios based on different regimes of water access and use. These scenarios should

be seen as the basic building blocks of the MC's function. By means of such scenarios, and by

working out the implications of current, probable or desirable trends, and through judicious use of

public information and advocacy tools, the MC can set the scene for a steady improvement in policy

formulation and decision making, and can provide an added incentive towards greater transparency

and participation in key decisions affecting water access and use.

· Development of policy options for consideration by decision makers on key issues related to the

management of the NWSAS. One of the central functions, based on the information in the

database, the application of the model, the scenarios developed, and the knowledge of national

positions and interests gathered from the dialogues or from the national steering mechanisms, is the

preparation of policy options for decision-makers. These options (proposed alternative strategies or

decisions) would focus on those issues most critical for promoting rational use of the water, and on

addressing the inevitable problems that will arise as the three countries seek to restrict use of the

aquifer to most essential purposes. The MC would thus serve as a kind of "decision support system"

to the authorities in the three countries.

· Providing a forum for discussion among water management authorities and those responsible

for agriculture, environment, regional development, etc. Given the nature of the NWSAS (deep

fossil water reserves), it is the hydrological authorities that hold the key to the aquifer. And yet it is

the decisions of the rural development, agriculture, housing, infrastructure and other parts of the

public administration, plus the behaviour of thousands of individual users that determine the pressure

on the water authorities to deliver the water they deem they need. This is an inimical situation, and

19

one it is necessary to understand very clearly. NWSAS has focused very centrally on how much

water there is, and at what rate it is being used. But the solutions have to come from the users

modulating their demand. A supply-side approach, on its own, will never work. Thus dialogue

among suppliers and demandeurs of water in the NWSAS basin is an essential part of future success.

Providing a forum for such discussions, identifying key topics, the most central actors, organizing

the events, and ensuring that the most relevant stakeholders are and remain engaged, is a very

compelling role for the MC.

Optional additional tasks

76.

The tasks spelled out above appear fundamental to maintaining the momentum towards cooperation

generated by the NWSAS project, and beginning to shift water use patterns in the basin onto a more rational basis.

It is difficult to imagine how, in the absence of these tasks being undertaken, the goal of the NWSAS can be

approached, much less met.

77.

The following seven are regarded as desirable additional tasks, to be undertaken to the extent that funding

can be identified. They are activities that could generate significant value added without the need to expend major

resources. But they are not essential, and would not find their way onto the list of priorities for a "bare-bones" MC.

· Preparation of briefing documents on themes of common interest, publication of regular

updates on these themes, operation of an early warning system for the three countries on issues

of importance to the optimal use of the NWSAS resource. One of the greatest dangers in any

field and any region is that the professional world begins to become self-enclosed. The MC could

provide constant intellectual and professional stimulation by preparing regular briefing notes on key

issues, literature surveys, annotated agendas, web-based bulletins or alert services, and many other

forms of cost-effective and uncomplicated service to the participating countries. These are typically

the sort of task assigned to a student, an intern or a young professional, and offer excellent return on

the investment.

· Publication of periodic reports on the state of the aquifer, trends, etc. This is no more than a

massaging of the data the MC will have to be working with in any event. It would seem to make

sense to entrust them with a regular "state of the resource" report, detecting emerging trends, threats,

encouraging developments, etc.

· Technical review of proposals for infrastructure, industrial or agricultural development,

human settlements, tourism or other major developments in terms of their likely impact on the

aquifer in the NWSAS zone. This goes a step beyond the semi-passive, coordination-based role for

the MC envisaged throughout this report. However, if it were politically feasible, it would be highly

desirable for all proposed large-scale developments in the NWSAS zone to be shared at the appraisal

stage with the other two countries, or for the MC to undertake a quick review (on a "right to

comment" basis) and to raise any warning flags necessary. Prevention is always better than cure.

· Organizing and managing capacity building and technical assistance services for authorities

and other organizations in the NWSAS zone. While the national water authorities can look after

the capacity and institutional development needs in their own countries, coming to a socially-

accepted standard for water access and use will involve introducing a range of skills and approaches

that are untried and unfamiliar in the three countries. As such, it is unlikely that the national

authorities, without stimulation from the outside, will give priority to mechanisms that, in some

senses, could end up challenging their traditional approaches and powers. To take an example from

the text above, it might be good to offer training on how to set up groundwater districts and user

groups. It would not be particularly difficult or time consuming for the MC to coordinate a modest

capacity development programme in this regard and it could pay large dividends in terms of meeting

the goal of rational use of the aquifer.

· Generation and promotion of ideas e.g. on sustainable agricultural practices, community

management of natural resources, resource access and governance, economic and fiscal incentives,

20

land reform, etc., including through monitoring interesting developments in other parts of the world.

To repeat a point made above, rational use of the NWSAS will require action on the demand side of

the equation, not simply regulating the supply of groundwater to all existing and potential users. The

world is full of experience on how to do that, and new ideas are generated every day. It would be

comparatively simple, and cost-effective, for the MC to monitor the literature, the relevant websites

and expert networks to harvest ideas that might have applicability to the NWSAS, and to disseminate

these through its regular channels of contact with the three countries involved.

· Conducting action-research on specific issues relating to the aquifer. While the responsibility

for further research lies principally with the national authorities, research institutions and

universities, and with their international partners, there will always be issues identified as critical but

still inadequately understood. While nobody believes the MC should evolve into an institution with

a robust research arm, it could be useful and cost-effective to give the MC a small fund to

commission occasional small-scale action-research interventions. The examples of the University

Fund and the Citizen's Fund operated by the Guaraní Aquifer authority are interesting in this regard.

· Providing an informal mechanism for consensus building, mediation and arbitration on issues

relating to management of the aquifer. As noted above, all mention of the MC serving as a

mechanism for conflict resolution raises acute sensitivities in the region. And yet the notion of

"concertation" connotes an alternative to competition and conflict, and is in itself an implied

contribution to achieving consensus, averting or sorting out areas of disagreement, and organizing a

process where win-win outcomes can be identified and pursued. Not to use the good offices of the

MC to take a first run at settling disputes appears to be a waste of an opportunity, even if it is simply

to forward these to an agreed and competent dispute settlement or mediation body. How far along

the route towards a deliberate role in conflict avoidance it should go is a matter for future debate.

78.

A note on sequencing: It should be clear from the above that the half-year remaining in this phase of the

project should be devoted to the detailed design of the MC and to the task of building consensus among the three

partners on its support and functioning. Both of these tasks are critical to consolidate what has been achieved in the

two phases of the NWSAS project and much work remains to be done. Despite the flurry of effort in the two-month

period between the Tripoli Steering Committee meeting in February and the OSS Governing Board meeting in

April, the design for the MC presented by the project team is still beset with problems, and is far from enjoying a

genuine consensus.

79.

It is recommended that, on the basis of their previous work, the experience of trying to rush through a

rapidly cobbled-together design, and the recommendations of this report, the team now devote a considerable and

concerted effort to achieve consensus around a design for the MC that is realistic, fundable, and that will ensure the

consolidation of the project's results in the longer term. They should also focus on the groundwork necessary to put

this mechanism into place by the project's end.

X.

Institutional models for the MC

80.

The Tripoli meeting discussed two models the "framework" and the "structure". The first is a minimalist

model, and the second implies the establishment of an institution, however modest. The Algiers meeting appeared

to move towards the notion of a framework (cadre) with a coordinator, and perhaps two junior staff. It is hard to

imagine the tasks listed above being undertaken by less than a full-time person with at least one assistant, and it

would appear desirable to take advantage of the opportunities offered by international volunteer, JPO or internship

programmes to supplement these skills on a cost-effective basis.

81.

The SASS project put forward a paper for the Algiers workshop entitled: "Mise en Place d'une

Commission Permanente du SASS" (attached at Annex 6). It called for the establishment of a permanent

coordination unit, supported by a Governing Board made up of the Directors-General of the water authorities from

the three countries, a Scientific Committee, and the occasional mandating of ad hoc working groups.

82.

While the over-structuring of the proposed MC set off alarm bells among those who envisage a light and

flexible structure, it is hard to envisage the successful operation of the MC without the continuing existence of the

21

three national steering committees, and their full engagement in the process something that has to date been